Ochratoxins are metabolites of Aspergillus, Fusarium, and Penicillium species. The most commonly implicated species are A. ochraceus and ostianus, P. viridicatum, griseofulvum and possibly solitum and Eurotium amstelodami (Ochratoxin, 2002).

Recent evidence shows that these mycotoxins are present in a variety of foods (cereals, pork, poultry, coffee, beer, wine, grape juice and milk). Analyses of these food products demonstrated that Ochratoxins are also produced by P. vercucosum and A. niger and carbonarius. (Abarca et al, 2001); Pitt, 2000; Bukelskiene et al, 2006).

There are three generally recognized Ochratoxins, designated A, B and C.

Ochratoxin A (OTA) is chlorinated and is the most toxic, followed by OTB and OTC. Chemically, they are described as 3,4-dihydro-methylisocoumarin derivative linked with an amide bond to the amino group of L-b-phenylalanine (Hussein et al, 2001).

The role and risk assessment of OTA in animal and human disease has been reviewed. The estimated tolerable dosage in humans was estimated at 0.2 to 4.2 ng/kg body weight based upon NTP carcinogenicity study in rats. OTA is mutagenic, immunosuppressive and teratogenic in several species of animals. Its target organs are the kidneys (nephropathy) and the developing nervous system (Kuiper-Goodman & Scott, 1989; Krogh, 1992).

Following intravenous administration, OTA is eliminated with a half-life from body in vervet monkeys in 19-21 days (Stander et al, 2001). There is no reason to suspect that the elimination half-life would be significantly different in humans.

OTA has been detected in human blood and milk. Other than nephropathy and urinary tumors, the evidence for human toxicology is scant. The toxicology of OTA will be briefly reviewed.

MECHANISM OF ACTION

Ochratoxin A has a number of toxic effects in animals. It is immunosuppressive, teratogenic, carcinogenic, nephrotoxic and neurotoxic. It inhibits protein synthesis, followed by inhibition of RNA synthesis. OTA lowers the level of phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase, a key enzyme in gluconeogenesis. The toxin also enhances lipid peroxidation both in vivo and in vitro, which is probably responsible for its adverse affects on mitochondrial function. OTA also forms DNA adducts in the kidney, liver and spleen that results in single-strand breaks (OTA, 2002).

CARCINOGENESIS

There is inadequate evidence that OTA is carcinogenic in humans. However, there is sufficient evidence in experimental animals. Overall, OTA is possibly carcinogenic to humans and is a Group 2B carcinogen.

Research Animals

Oral administration of OTA produced tubular cell carcinomas of the kidneys in male and female rats and fibro adenomas of the mammary gland in the females (Ochratoxin, 2002).

Administration of OTA in the diet of ddy mice produced tumors of kidneys--solid renal tumors and cystic adenomas. Also, hepatic-tumors and hyperplastic liver nodules were found and unspecified lung tumors.

In addition, solid renal-cell tumors occurred in ddy mice fed OTA in their diet(Ochratoxin A, 2000).

Male and female Fischer rats given oral doses of OTA had dose-related increases in kidney tumors--renal-cell adenomas, and renal-cell adenoma-carcinomas. Metastasis of the renal cell tumors occurred in 17 males and one female (Ochratoxin A, 2002).

Humans

Balkan endemic neuropathy (BEN) associated with OTA occurs in Europe (Bulgaria, Croatia, Turkey, Egypt, and Yugoslavia) where OTA is relatively high in the diet. Individuals with BEN were surveyed for the presence of urinary tract tumors. The incidence of tumors in the urinary system was elevated in both men and women. Furthermore, the observations suggested that individuals with urinary tract tumors had elevated levels of OTA in the blood and urine. Approximately one-third of patients dying from BEN have papillomas and/or carcinomas of the renal pelvis, ureter or bladder (Ochratoxin, 2002; Radovanovic et al, 1991;, Wafa et al, 1997; Radic et al, 1997; Ozcelik et al, 2001; Pfohl-Leszkowicz et al, 2002).

Recently, it has been suggested that OTA can cause testicular cancer in humans (Schwartz, 2002). The hypothesis that consumption of foods contaminated with OTA causes testicular cancer was tested. The incidence of rates of testicular cancer in 20 countries was significantly correlated with the per-capita consumption of coffee and pig meat.

Schwartz concluded: "Thus, OTA is a biologically plausible cause of testicular cancer. Future epidemiologic studies of testicular cancer should focus on the consumption of OTA-containing foods such as cereals, pork products, milk and coffee by mothers and their male children."

TERATOGENESIS and MUTAGENESIS

OTA crosses the placenta and is also transferred to newborn rats and mice via lactation (Hallen et al, 1998). In addition, OTA-DNA adducts are formed in liver, kidney and other tissues of the progeny (Petkova-Bocharova et al, 1998; Pfohl-Leszkowicz et al, 1993). This is significant in light of the fact that OTA causes birth defects in rodents.

In mice, damage to the neural plates and folds, mid-brain and fore-brain was reported in one study while a second one showed cell death in the telencephalon (Ochratoxin A, 2002).

Other abnormalities included necrosis of the brain (mice); fetal resorption and visceral and skeletal defects (rats, mice and hamster (Ochratoxin A, 2002; Singh & Hood, 1985); craniofacial (exenoephaly, midfacial and lip clefts, hypotelorism and synopthalmia), body wall malformations in mice (Wei & Sulik, 1993) and a reduction of synapses per neuron in the somatosenscry cortex of mice (Fukui et la, 1992).

Finally, prenatal exposure of rats results in suppressed lymphocyte mitogenic response to lipopolysaccharide and Con A that lasts through at least 13 weeks of age (Thunder et al, 1995). Thus, sufficient experimental evidence exists in the scientific literature to classify OTA as a teratogen, affecting both the nervous system, skeletal structures and immune system of research animals.

IMMUNOSUPPRESSION

OTA causes immunosuppression following prenatal, postnatal and adult-life exposures. These effects include reduced phagocytosis and lymphocyte markers (pig weaners) (Muller et al, 1999), increased susceptibility to bacterial infections and delayed response to immunization in piglets (Stoev et al, 2000) In adult mice, NK cell activity is suppressed by CIA (Luster et al, 1981).

Purified human lymphocyte populations and subpopulations are adversely affected by OTA in vitro Lea et al, 1989). Both IL- production and IL-2 receptor expression on activated T cells are severely impaired by OTA and not OTB. The inhibitory action of OTA is reversed in the presence of OTB.

Further, B cells do not respond to polyclonal activators following a brief exposure to OTA. The authors suggest that the toxin causes immunosuppression through interference with essential processes of cell metabolism (see mitochondria below) irrespective of lymphocyte population or subpopulation.

MITOCHONDRIA

Several lines of experimental observations demonstrate that OTA effects mitochondrial function and causes mitochondrial damage. The reader is referred to Wallace (1997) for background information on mitochondrial DNA in aging and disease in chicks and quail.

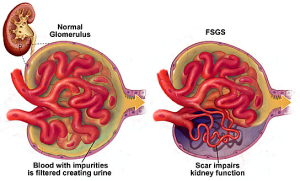

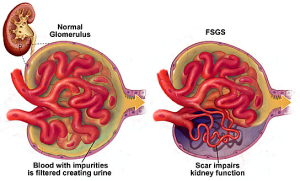

OTA causes pathological changes in the ultra structure of mitochondria in proximal convoluted tubules and glomeruli of kidneys and liver. These changes include abnormal shapes, enlarged mitochondrial matrix and excessive lipid droplets (Brown et al, 1986; Dwivedi et al, 1984; Maxwell et al, 1981).

OTA causes oxidative stress and production of free radicals in rat hepatocytes and proximal tubules of the kidneys. Lipid peroxidation preceded cell death in cells of the proximal tubules (Gautier et al, 2002; Hoehler et al, 1997).

OTA is a nonoompetitive inhibitor of both succinate-cytochrome C reductase and succi nate dehydrogenase. It impairs mitochondrial respiration and oxidative phorphorylation through impairment of the mitochondrial membrane and by inhibition of suoci nature-supported electron transfer activities of the respiratory chain (Wei et al, 1985). It also inhibits glutamateimalate substrate respiration of Site I and causes lipid peroxidation leading to cell death (Alec et al, 1991.

Another mechanism appears to be the activation of mitochondrial NHE interfering with Ca2+ homeostasis. This induces extracellular acidification leading to cell death in renal proximal tubules (Eder et al, 2000; Rodeheaver & Schnellman, 1993).

DNA, PROTEIN and RNA

OTA is mutagenic and carcinogenic (Ochratoxin A, 2002). It causes DNA single-stranded breaks and DNA adducts in the DNA of spleen, liver and kidney in OTA treated mice (Pfohl-Leszkowicz et al, 1991; Creppy et al, 1985).

OTA inhibits bacterial, yeast and liver phenylalanyl-tRNA synthetases. The inhibition is competitive to phenylalanine and is reversed by an excess of this amino acid. It also inhibits phenylalanine hydroxylase and lowers the concentration of phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase. It appears that an inhibition of protein and RNA synthesis is the end result of these toxic effects (Dirheimer & Creppy, 1991). Inhibition of protein and RNA synthesis is considered one of the toxic effects of OTA (Ochratoxin A, 2002).

APOPTOSIS

OTA induces apoptosis (programmed cell death) in a variety of cell types in vivo and in vitro. The mechanisms include caspase 3 activation, mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK) family, and c-jun amino-terminal kinase (JNK). The apoptosis is also mediated through cellular processes involved in the degradation of DNA. Finally, the mechanisms leading to cell death may be inhibited by various antioxidants (Atroshi et al, 2000; Gekle et al, 2000; Schwerdt et al, 1999; Seegers et al, 1994).

BALKAN ENDEMIC NEPHROPATHY

OTA is nephrotoxic in all animals studied and has been implicated in the etiology of Balkan endemic nephropathy (BEN) (Ochratoxin A, 2002). The clinical picture of BEN is that of a slowly progressing tubulo-interstitial chronic nephritis and urethral tumors are frequent, occurring in 2-47 % of cases (Radonic & Radosevic, 1992). The proximal tubule cells are the primary target for OTA toxicity. BEN is an end-stage renal disease.

Epidemiological investigations have shown that BEN and dietary exposure are associated, leading to the conclusion that OTA is one of the causative agents in the identification of DNA-ochratoxin A adducts in urinary tract tumors in patients from areas with BEN add support to this conclusion (Puntaric et al, 2002; Stoev et al, 1998; Pfohl-Leszkowicz et al, 1993b; Mikolov et al, 1996).

CONCLUSIONS

OTA is a mycotoxin produced by species of Eurotium, Aspergillus, Fusarium and Penicillium. It is found in many food crops, including cereals, coffee, cocoa and dried vine fruits.

OTA is mutagenic, carcinogenic, teratogenic and immunosuppressive in a variety of animal species. It has been implicated in the etiology of BEN and urinary tract tumors in humans.

It is a mitochondrial poison causing mitochondrial damage, oxidative burst, lipid peroxidation and interferes with oxidative phosphorylation. In addition, OTA increases apoptosis in several cell types.

The UK's Joint Expert Committee on Food Additives has set a provisional tolerable dietary intake (TDI) of 0.2 mg/kg body weight per week.

OTA has been found in human and cow milk samples in European countries (Ochratoxin A, 2002).

In Norway, the concentrations found in human and cow milk were sufficient to suggest that the TDI of 5 ng/kg body/day would be exceeded in small children who consume large quantities of milk (Skaug et al, 1990, 1999, 2001).

Airborne exposure to OTA can occur, adding to the daily intake of the mycotoxin via the respiratory tract. Thus, OTA has been demonstrated in dust and fungal conidia in samples taken from cow sheds.

Furthermore, OTA was detected in dust samples from the heating ducts of a house where animals showed signs of ochratoxicosis (Skaug et al, 2000; Richard, 1999).

Finally, Ochratoxin A has been found in bulk samples of a water-damaged home. In addition, the occupants and the household dog had Ochratoxin A in urine and nasal secretions (Thrasher, et al, 2010).

References

Abarca ML et al (2001) Current importance of Ochratoxin A-producing Aspergillus spp. Food Prot 64:903.

Aleo et al (1991) Mitochondrial dysfunction is an early event in ochratoxin A but not oosporein toxicity to rat renal proximal tubules. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 107:73.

Atroshi F et al (2000) Significance of apoptosis and its relationship to antioxidants after ochratoxin A administration in mice. J Pharm Pharm Sci 3:281.

Brown TP et al (1986) The individual and combined effects of citrinin and ochratoxin A on renal ultrastructure in layer chicks. Avian Dis 30:191.

Creppy EE, et al (1985) Genotoxicity of ochratoxin A in mice: DNA single-strand breaks evaluation in spleen, liver and kidney. Toxicol Lett 28:29.

Dirheimer G, Creppy EE (1991) Mechanism of action of ochratoxin A. IARC Sci Publ 1991(115):171.

Dwivedi P et al (1984) Ultrastructural study of the liver and kidney in ochratoxicosis A in young broiler chicks. Res Vet Sci 36:104.

Eder S et al (2000) Nephritogenic ochratoxin A interferes with mitochondrial function and pH homeostatis in immortalized human kidney epithelial cells. Pflugers Arch 440:521.

Gautier JC et al (2001) Oxidative damage and stress response from ochratoxin A exposures in rats. Free Radic Biol Med 30:1089.

Gekle M et al (2000) Ochratoxin A induces JNK activation and apoptosis in MDCK-C7 cells at nanomolar concentrations. J Pharmacol Exper Ther 293:837.

Hallen IP et al (1998) Placental and lactational transfer of ochratoxin A in rats. Nat Toxins 6:43.

Hoehler D et al (1997) Induction of free radicals in hepatocytes, mitochondria and microsomes of rats by ochratoxin A and its analogs. Biochim Biophys Acta 1357:225.

Hussein S et al (2001) Toxicity, metabolism, and impact of mycotoxins on humans and animals. Toxicology 101:134.

Bukelskiene V, Baltriukiene D, Repeckiene J (2006) Study of the health risks of Aspergillus amstelodami and its mycotoxin effects. Ekologia 3:42-7.

Fukui Y et al (1992) Development of neurons and synapses in ochratoxin A-induced microcephalic mice: a quantitative assessment of somatosensory cortex. Neurotoxicol Teratol 14:191.

Krogh P (1992) Role of ochratoxin in disease causation. Food Chem Toxicol 30:213.

Kuiper-Goodman T, Scott PM (1989) Risk assessment of the mycotoxin Ochratoxin A. Biomed Environ Sci 2:179.

Lea T et al (1989) Mechanism of ochratoxin A-induced immunosuppression. Mycopathologia 107:153.

Luster MH et al (1987) Selective immunosuppression in mice of natural killer cell activity by ochratoxin A. Cancer Res 47:2259.

Maxwell MH et al (1987) Ultrastructural study of ochratoxicosis in quail (Corunix corunix japonica). Res Vet Sci 42:228.

Mikolov IG et al (1996) Molecular and epidemiological approaches to the etiology of urinary tract tumors in an area with Balkan endemic nephropathy. Environ Pathol Toxicol Oncol 15:201.

Muller G et al (1999) Studies of the influence of ochratoxin A on immune and defense reactions in weaners. Mycoses 42:495.

Ochratoxin A (2002) National Library of Medicine. Hazardous Substance Data Base. Toxnet (National Data Network).

Ozcelik N et al (2001) Ochratoxin A in human serum samples collected in Isparta-Turkey from healthy individuals and individuals suffering from different urinary tract disorders. Toxicol Lett 121:9.

Petkova-Bocharova T et al (1998) Formation of DNA adducts in tissues of mouse progeny through transplacental contamination and/or lactation after administration of a single dose of ochratoxin A to the pregnant mother. Environ Mol Mutagen 32:155.

Pfohl-Leszkowicz et al (1991) DNA adduct formation in mice treated with ochratoxin A. IARC Sci Pub 1991(115):245.

Pfohl-Leszkowicz A et al (1993) Differential DNA adduct formation and disappearance in three mice tissues after treatment by the mycotoxin, ochratoxin A. Mutat Res 289:265.

Pfohl-Leszkowicz A et al (1993b) Ochratoxin A-related DNA adducts in urinary tract tumours of Bulgarian subjects. IARC Sci Pub 124):141.

Pfohl-Leszkowicz A et al (2002) Balkan endemic nephropathy and associated urinary tract tumours: a review on aetiological causes and the potential role of mycotoxins. Food Addit Contam 19:282.

Pitt JI (2000) Toxigenic fungi: which are important. Med Mycol 38 (Suppl 1):17.

Puntaric D et al (2001) Ochratoxin A in corn and wheat: geographical association with endemic nephropathy. Croat Med J 42:175.

Radic B et al (1997) Ochratoxin A in human sera in the area of endemic nephropathy in Croatia. Toxicol Lett 91:105.

Radonic M, Radosevic Z (1992) Clinical features of Balkan endemic nephropathy. Food Chem Toxicol 30:189.

Radovanovic A, et al (1991) Incidence of tumors of urinary origin in a focus of Balkan endemic nephropathy. Kidney Inter Suppl. 34:S75. Schwartz GG (2002) Hypothesis: Does ochratoxin A cause testicular cancer? Cancer Causes and Control 13:91.

Richard JL (1999) The occurrence of ochratoxin A in dust collected from a problem household. Mycopathologia 146:99 .

Rodeheaver DP, Schnellman RG (1993) Extracellular acidosis ameliorates metabolic-inhibitor-induced and potentiates oxidant-induced cell death in renal proximal tubules. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 265:1355.

Schwerdt G et al (1999) The nephrotoxin ochratoxin A induces apoptosis in culture human proximal tubule cells. Cell Biol Toxicol 15:405.

Seegers JC et al (1994) A comparative study of ochratoxin A-induced apoptosis in hamster kidney and HeLa cells. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 129:1.

Singh J, Hood RD (1985) Maternal protein deprivation enhances the teratogenecity of ochratoxin A in mice. Toxicology 32:381.

Skaug MA et al (1998) Ochratoxin A: a naturally occurring mycotoxin found in human milk samples from Norway. Acta Paediatr 87:1275.

Skaug MA (1999) Analysis of Norwegian milk and infant formulas for ochratoxin A. Food Addit Contam 16:75.

Skaug MA et al (2001) Presence of ochratoxin A in human milk in relation to dietary intake. Food Addit Contam 18:321.

Skaug MA et al (2000) Ochratoxin A in airborne dust and fungal conidia. Mycophathologia 151:93.

Stander MA et al (2001) Toxicokinetics of ochratoxin A in vervet monkeys (Cericopithecus aethiops). Arch Toxicol 75:262.Wafa EW et al (1997) Human Ochratoxicosis and nephropathy in Egypt: A preliminary study. Human Exp Toxicol 17:124.

Stoev SD et al (2000) Susceptibility to secondary bacterial infections in growing pigs as an early response to ochratoxicosis. Exp Toxicol Pathol 52:287.

Stoev SD (1998) The role of ochratoxin A as a possible cause of Balkan endemic nephropathy and its risk evaluation. Vet Hum Toxicol 40:352.

Thrasher JD, Hooper D, Kilburn KH (2010) Mycotoxins identified bulk, in nasal and urine samples from occupants in a water damaged home (manuscript in preparation).

Thuvander A et al (1996) Effects of ochratoxin A on the rat immune system after perinatal exposure. Nat Toxins 4:141.

Wafa EW et al (1997) Human ochratoxicosis and nephropathy in Egypt: A preliminary study. Human Exp Toxicol 17:124.

Wallace DC (1997) Mitochondrial DNA in aging and disease. Scientific American, August, pp 40-47.

Wei X, Sulik KK (1993) Pathogenesis of craniofacial and body wall malformations induced by ochratoxin A in mice. Am J Med Genet 47:862.

Wei YH et al (1985) Effect of ochratoxin A on rat liver mitochondrial respiration and oxidative phosphorylation. Toxicology 36:119.