Sarcoidosis is a disease that can involve all organs of the body. The causes of the disease are slowly being revealed in the current scientific and medical literature.

Sarcoidosis is a granulomatous inflammatory disease that occurs in lymph nodes, lungs, liver, eyes, skin, joints, brain and other organs. The inflammation results in granulomas in these organs that are driven by TH1/TH17 lymphocytes, dendritic cells, chemokines and pro-inflammatory cytokines.

Who has Sarcoidosis?

Once thought rare, sarcoidosis is now known to be common and affects people worldwide. The disease can affect people of any age, race and gender. However, it is most common among adults between the ages of 20 and 40 and in certain ethnic groups.

- In the United States, it is most common in African Americans and people of European "particularly Scandinavian" descent.

- Among African Americans, the most affected U.S. group, the estimated lifetime risk of developing sarcoidosis might be as high as 2 percent.

- Most studies suggest a higher disease rate for women.

Disease severity can vary by race or ethnicity.- Higher among African Americans than among Caucasians.

- Appearance of the disease outside of the lung is common in certain populations. For example: the eyes (chronic uveitis) in African Americans, painful skin lumps in Northern Europeans, and the heart and eyes in Japanese.

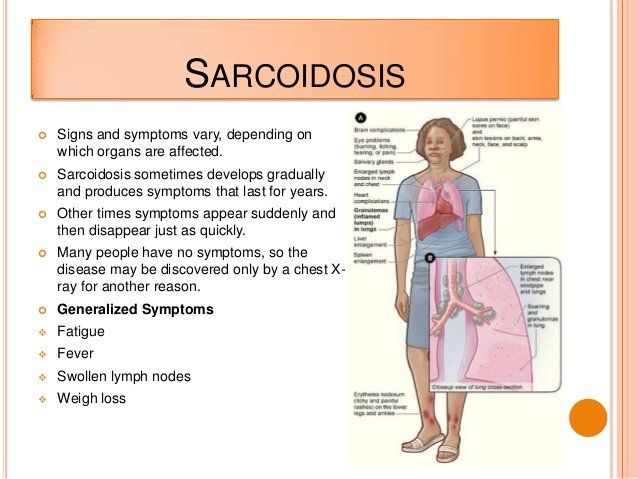

What are the Symptoms?

Sarcoidosis is a multi-system disorder. Symptoms typically depend on which organ the disease affects. Most often, the disease will affect the lungs. The symptoms and organs involved in sarcoidosis can vary from individual to individual.

- General: About one third of patients will experience non-specific symptoms of fever, fatigue, weight loss, night sweats and an overall feeling of malaise (or ill health).

- Lungs: The lungs are affected in more than 90% of patients with sarcoidosis. A cough that does not go away, shortness of breath, particularly with exertion and chest pain occur most frequently with the pulmonary form of the disease.

- Lymph Nodes: Up to 90% of sarcoidosis patients have enlarged lymph nodes. Most often they are in the neck, but those under the chin, in the arm pits and in the groin can be affected. The spleen, which is part of the lymphatic system, can also be affected.

- Liver: Although between 50% to 80% of patients with sarcoidosis will have granulomas in their liver, most are without symptoms and do not require treatment.

- Heart: Researchers estimate that cardiac sarcoidosis, affects more than 10 percent of people with sarcoidosis in the United States, and perhaps as many as 25 percent. Sarcoidosis can cause the heart to beat weakly resulting in shortness of breath and swelling in the legs. It can also cause palpitations (irregular heartbeat).

- Brain & Nervous System: From 5% to 13% of patients have neurologic disease. Symptoms can include headaches, visual problems, weakness or numbness of an arm or leg and facial palsy.

- Skin: One in four (25%) patients will have skin involvement. Painful or red, raised bumps on the legs or arms (called erythema nodosum), discoloration of the nose, cheeks, lips and ears (called lupus pernio) or small brownish and painless skin patches are symptoms of the cutaneous form of the disease.

- Bones, Joints & Muscles: Joint pain occurs in about one-third of patients. Other symptoms include a mass in the muscle, muscle weakness and arthritis in the joints of the ankles, knees, elbows, wrists, hands and feet.

- Eyes: Any part of the eye can be affected by sarcoidosis and about 25% of patients have ocular involvement. Common symptoms include: burning, itching, tearing, pain, red eye, sensitivity to light (photophobia), dryness, seeing black spots (called floaters) and blurred vision. Chronic uveitis (inflammation of the membranes or uvea of the eye) can lead to glaucoma, cataracts and blindness.

- Sinuses, Nasal Muscosa (lining) & Larynx: About 5% of patients will have involvement in the sinuses with symptoms that can include sinusitis, hoarseness or shortness of breath.

- Other Organs: Rarely, the gastrointestinal tract, reproductive organs, salivary glands and the kidneys are affected.

Diagnosis

Physical examination may reveal the following: enlarged liver and spleen, enlarged lymph nodes (neck and axillary), skin rashes or sores.

Symptoms of sarcoidosis can mimic those of other diseases. In some cases, sarcoidosis may be diagnosed by excluding these other similar diseases. Frequently, sarcoidosis is diagnosed because a routine chest x-ray shows an abnormality. To accurately diagnose the disease, most doctors will take a medical history and perform a physical examination. Laboratory tests of the blood, chest x-rays, breathing tests and biopsy are all diagnostic tools.

The disease can be progressive (e.g., beginning with stage I through IV). Stage IV is almost always systemic.

References

1. Berge BT, Kleinjan A, Muskens F, Hammad H, et al. 2012. Evidence for local dendritic cell activation in pulmonary sarcoidosis. Respir Res 13:33.

2. D’Angel C, De Luca A, Zelante T, Bonifazi P et al. 2009. Exogenous pentraxin 3 restores antifungal resistance and restrains inflammation in murine chronic granulomatous disease. J Immunol 183:4609-18.

3. Facco M, Basesso L, Miorin M, Bortoli M, et al. 2007. Expression of CCR/CCL20 chemokine axis in pulmonary sarcoidosis. J Leukocyte Biol 82:946-55.

4. Gupta D, Agarwal R, Agarwal AN, Verma I. 2011. Immune responses to mycobacterial antigens in sarcoidosis: A systematic review. 53:41-9.

5. Tercelj m, Stopinsek S, Ihan A, Salobir B et al. 2011. In vitro and in vivo reactivity to fungal cell wall agents in sarcoidosis. Clin Exper Immunol 166:87-93.

6. Zelante T, Bozza S, De Luca A, D’Angelo C et al. 2009. Th 17 in the setting of Aspergillus infection and pathology. 47 (Suppl 1) S162-9.

7. Zelante T, De Luca A, Bonifazi P, Montagnoli C, et al. 2007. Il-23 and the Th 17 pathway promote inflammation and impair antifungal immune resistance. Eyr J Immunol 37:2695-706.